Heat transfer

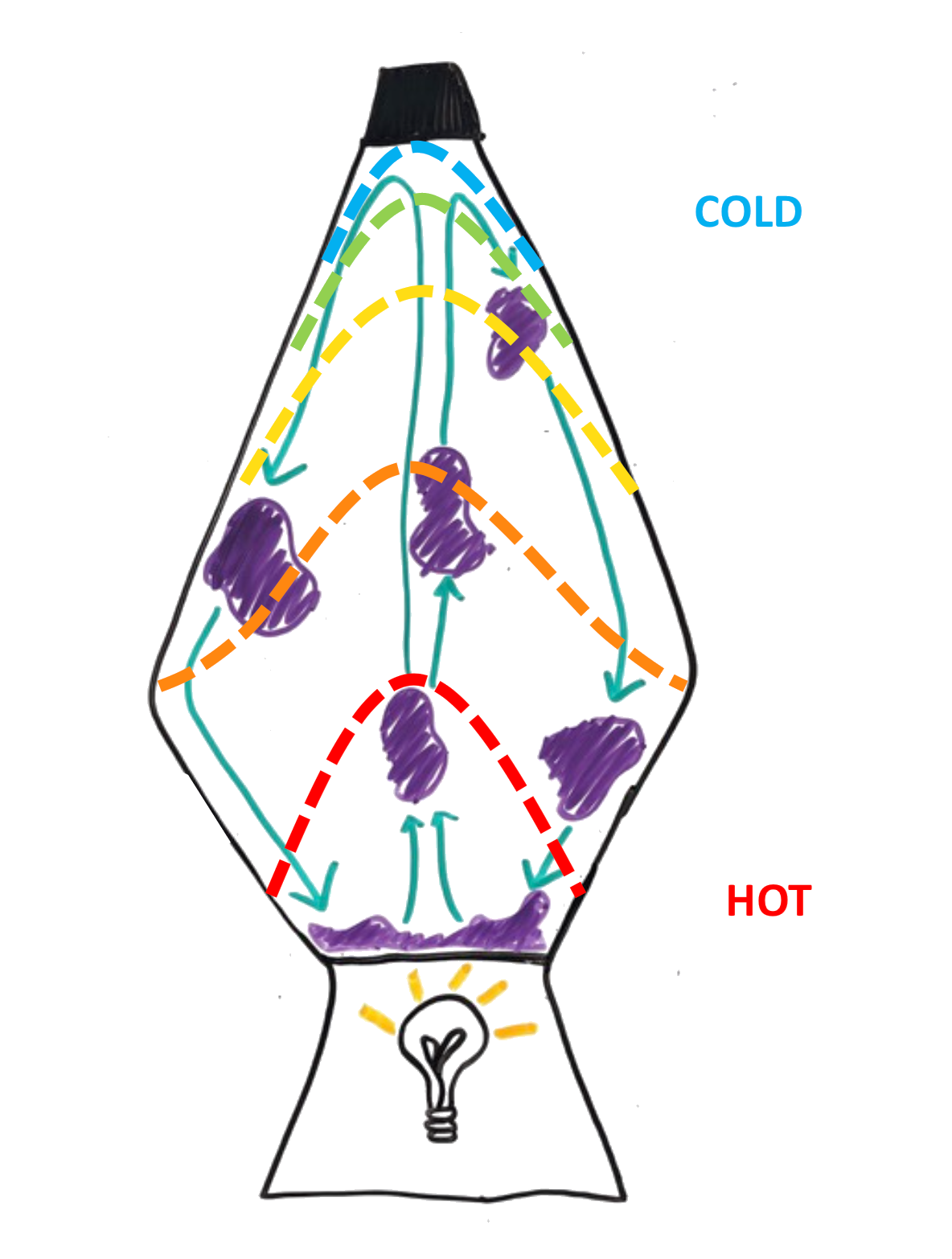

Heat Transfer in a Lava Lamp

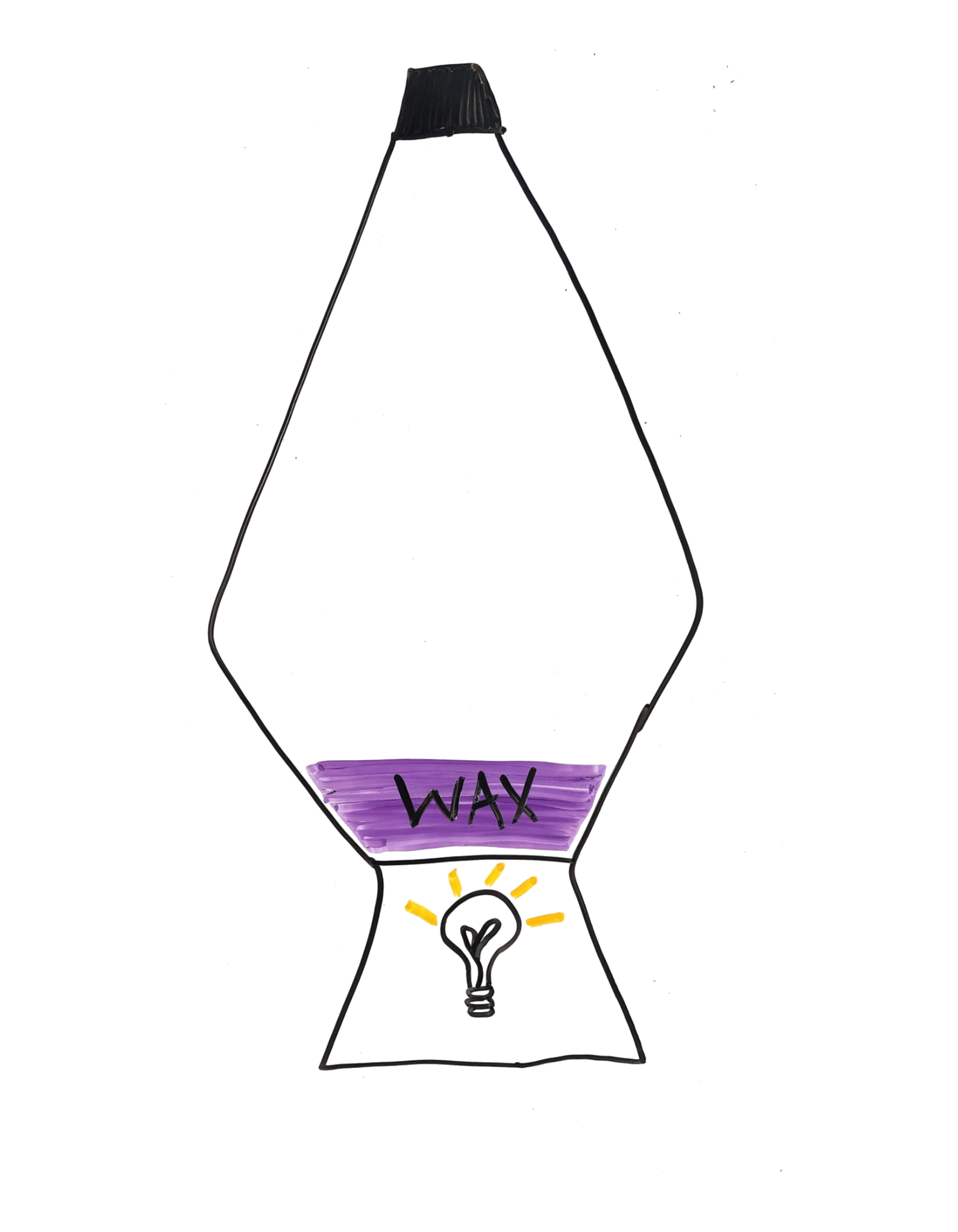

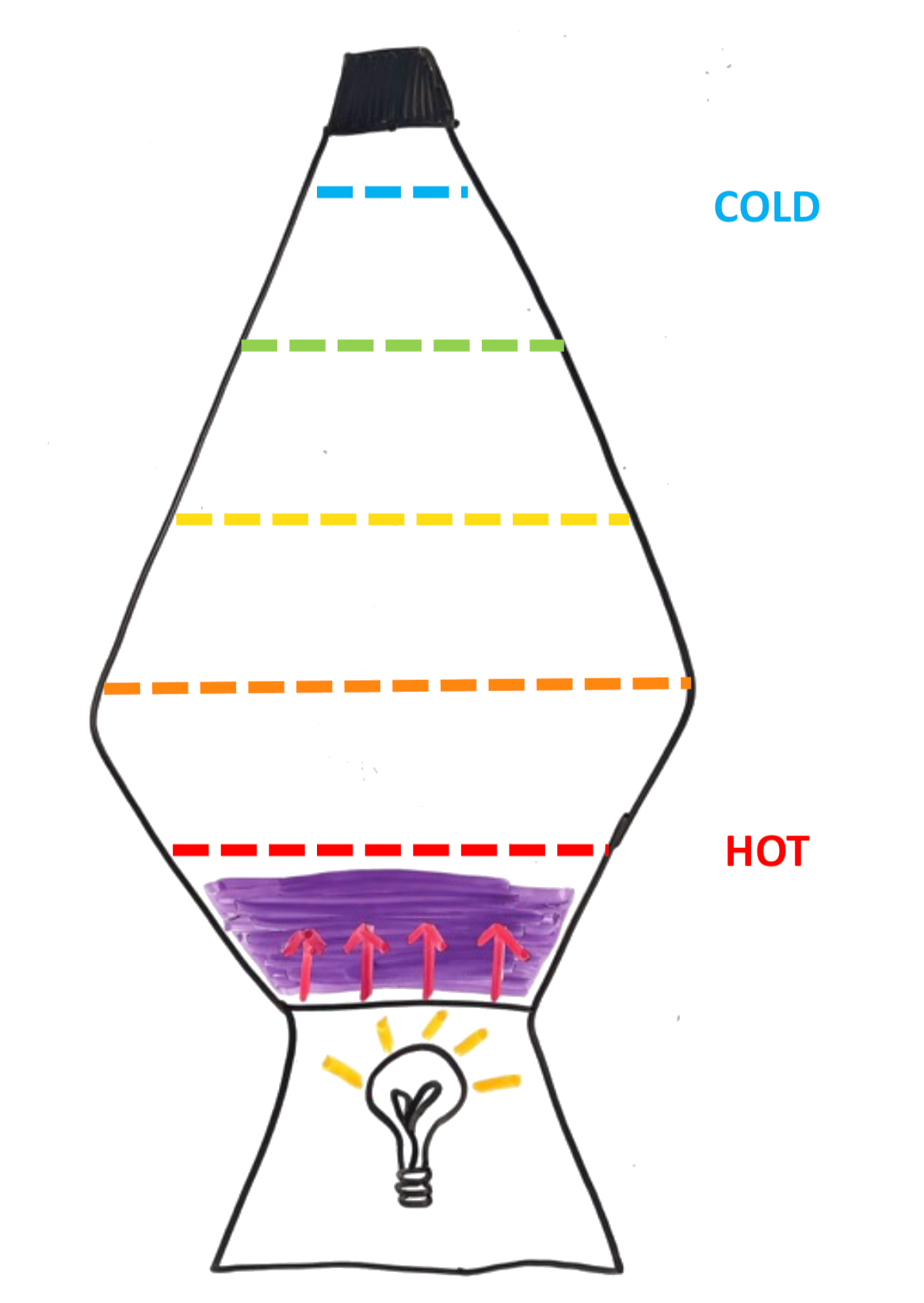

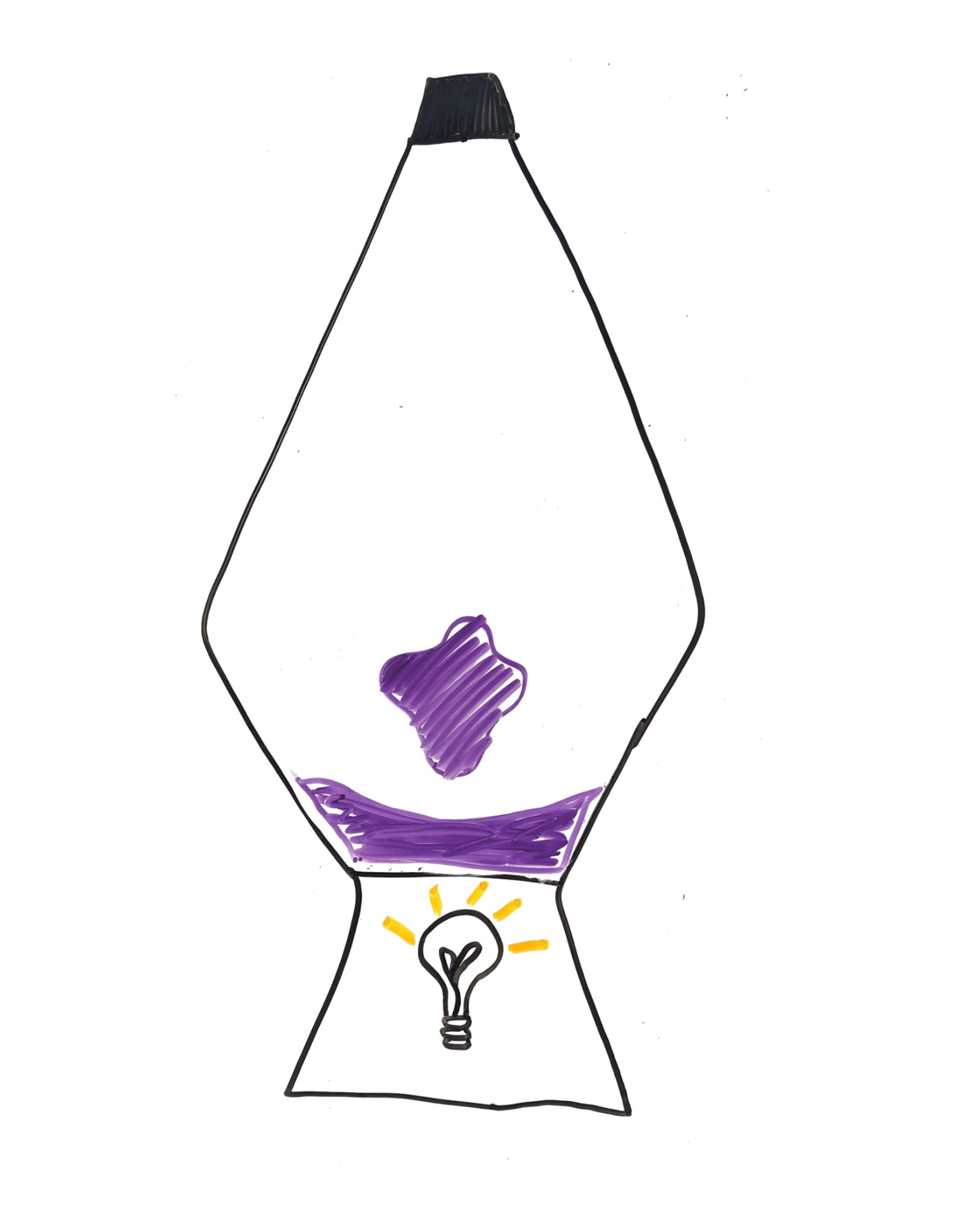

When you flip on the light in a lava lamp, heat from the bulb works slowly to warm up the wax (or ‘lava’). This kind of heat transfer is called conduction, or movement of heat from one place to another. Heat energy flows from high heat (light bulb) to low heat (wax), and the gradient is the driver of conductive heat transfer.

Until things start moving, conduction is the dominant heat transfer process in our lava lamp system.

- Conduction, defined as κ∇²T depends on:

- thermal diffusivity of the material through which heat is moving (κ)

- thermal gradient (∇²T)

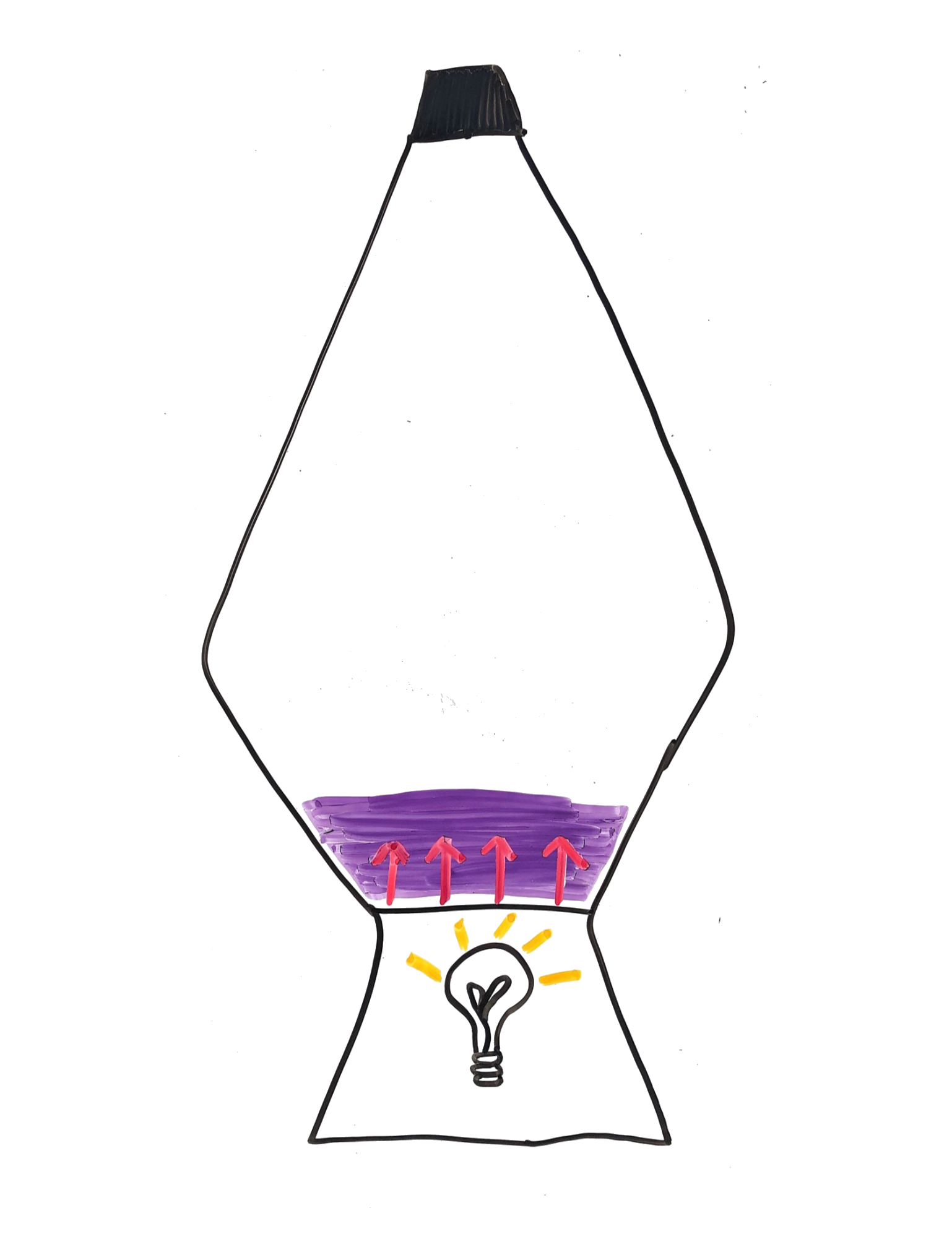

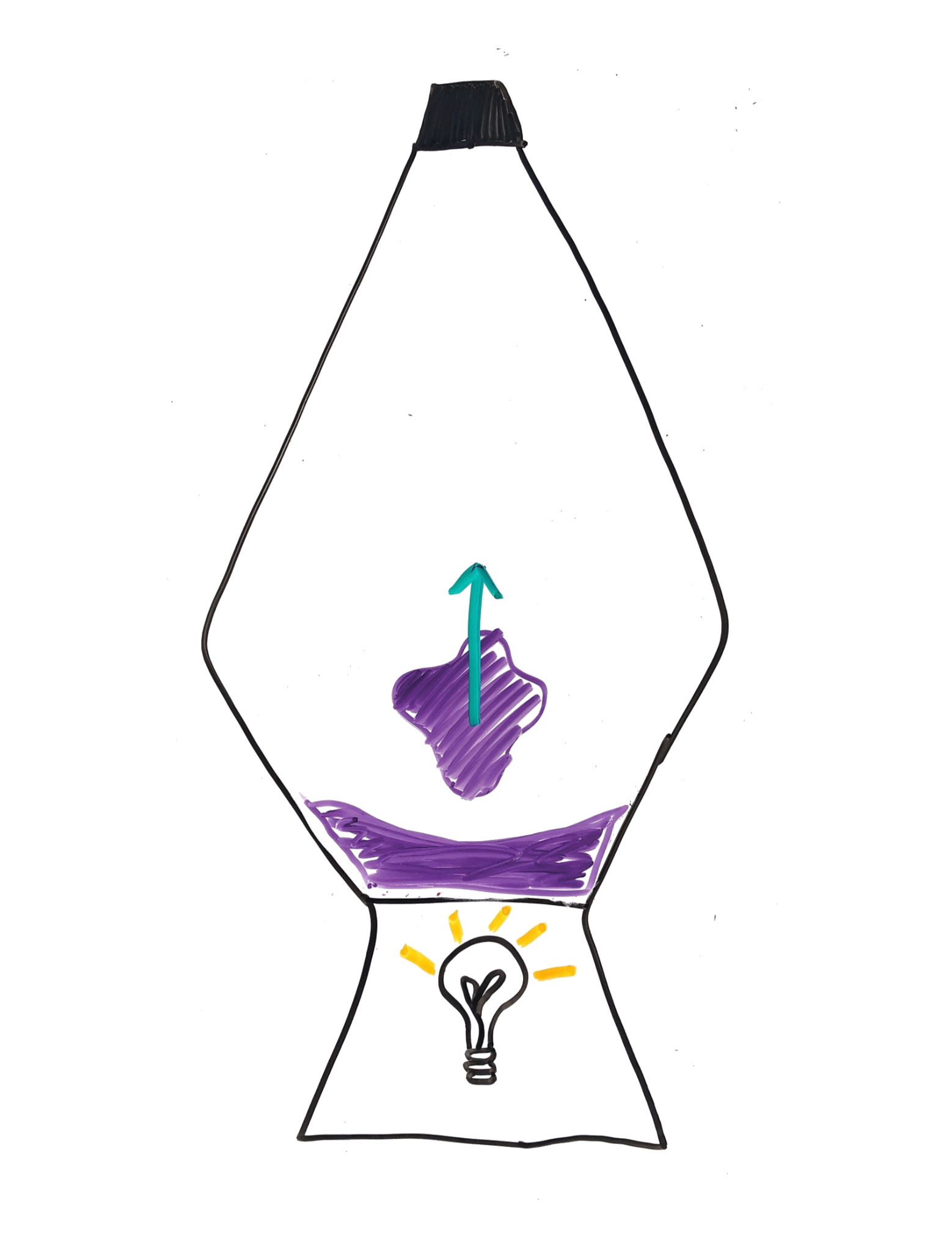

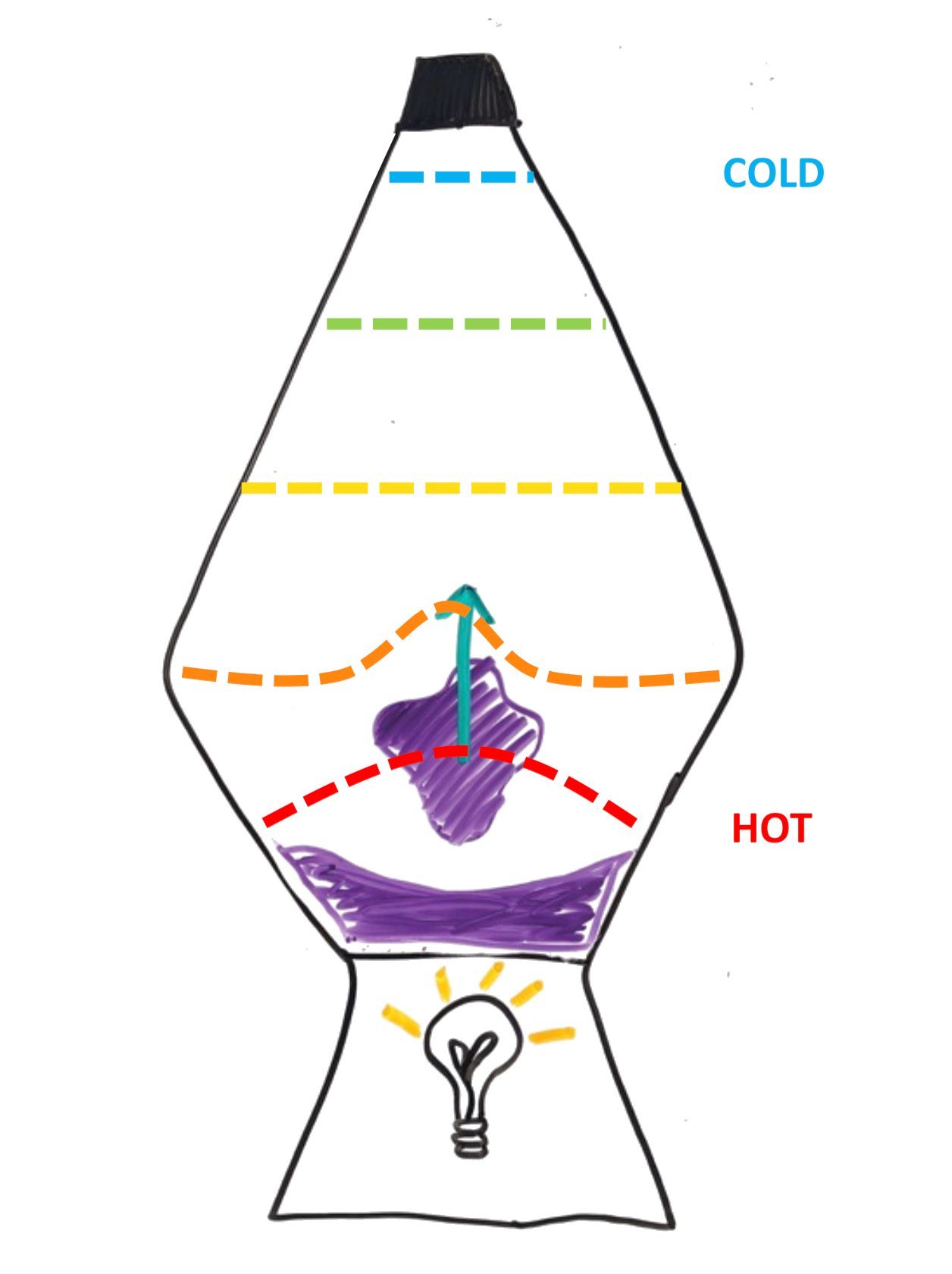

The density of the wax is inversely related to temperature, meaning that at higher temperatures, the wax is less dense. When the density becomes lower than the density of the liquid in the lava lamp, the wax will tend to float upward.

Wax reaches critical density (less than liquid) and tends to float upward. That movement of wax, and thus heat, introduces velocity into the system and is a process that is referred to as advection.

- Advection, defined as v∇T depends on:

- velocity of the fluid (v)

- thermal gradient (∇T)

Heat Transfer Equation:

Heat transfer within the lava lamp can be represented by an equation. The heat transfer equation brings these aforementioned processes together to describe how heat changes through time (∂T/∂t). It is defined as:

∂T/∂t = κ∇²T + v∇T + A

∂T/∂t = conduction + advection + production

The production term (A) represents internally generated heat energy and we do not consider it in this lava lamp scenario. It becomes important in systems such as glaciers, when internal strain heating is an important source of heat.

Peclét Number:

The Peclét Number is a dimensionless number which indicates whether conduction or advection dominates the system.

Pe = uL/κ

where u = flow velocity, L = characteristic length Height of lava lamp, κ = thermal diffusivity

- Low peclet regime- dominated by heat transport by conduction

- High peclet regime- dominated by heat transport by advection

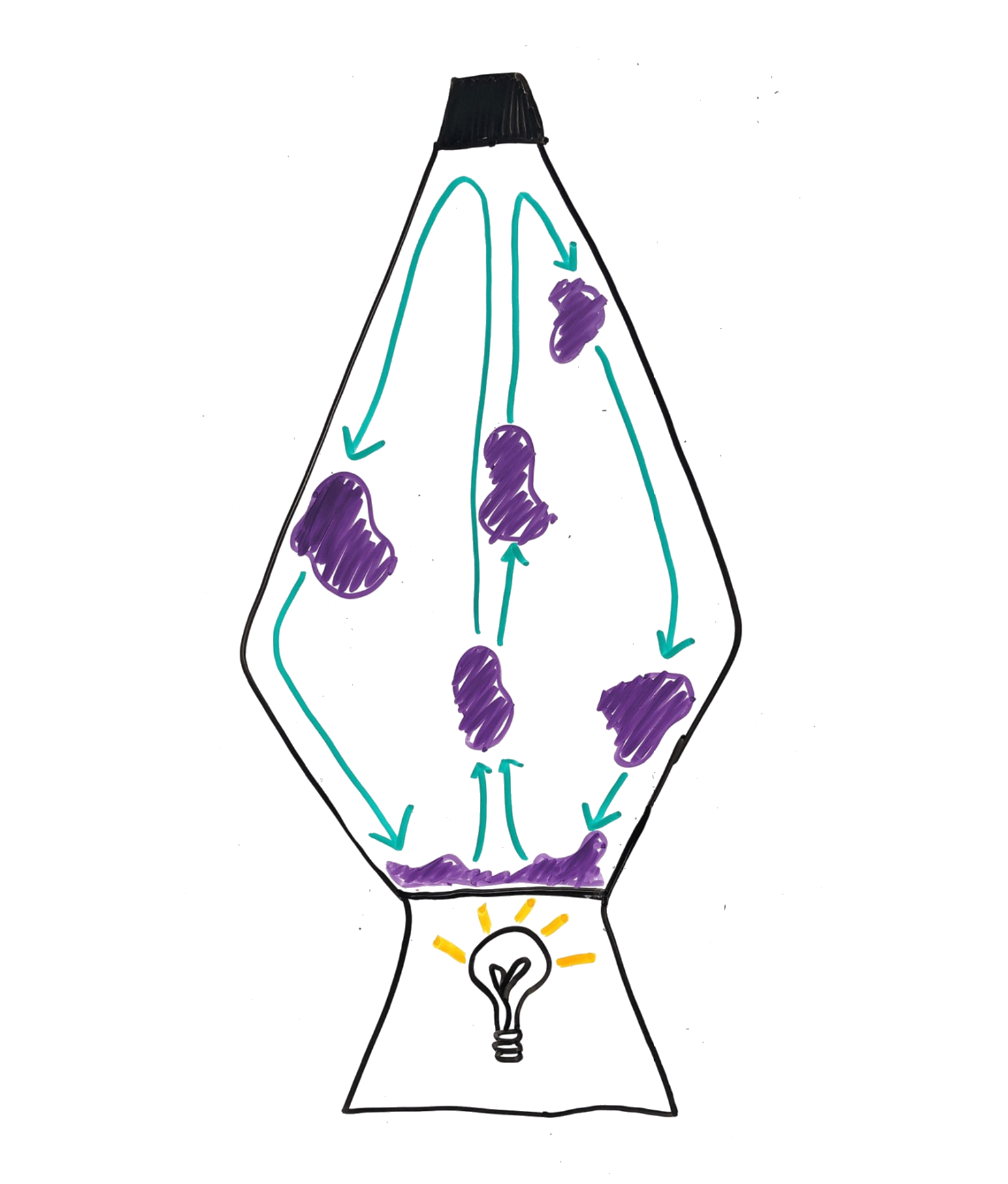

With the movement of wax in the upward direction away from the heat source at the bottom of the container and into a cooler material the wax density increases again (more than liquid). This wax density increase causes the wax to sink back down to the bottom of the container towards the heat source. This process is called convection.

Rayleigh Number:

The Rayleigh Number is a dimensionless number used to describe whether convection grows or decays.

Ra ≡ (gρΔTαd³)/μκ

- Convection depends on driving forces and resisting forces.

- Driving forces (when these terms are dominant convection grows):

- Acceleration due to gravity (g)

- Density (ρ)

- The temperature difference between the bottom and top of the convection cell (ΔT)

- The volume coefficient of thermal expansion (α)

- The height of the convection cell (d)

- Resisting forces (when these terms are dominant convection decays):

- Viscosity (μ)

- Thermal diffusivity (κ)

- Driving forces (when these terms are dominant convection grows):

At some critical Rayleigh (Racr) number (dependent on the system), the convection regime shifts.

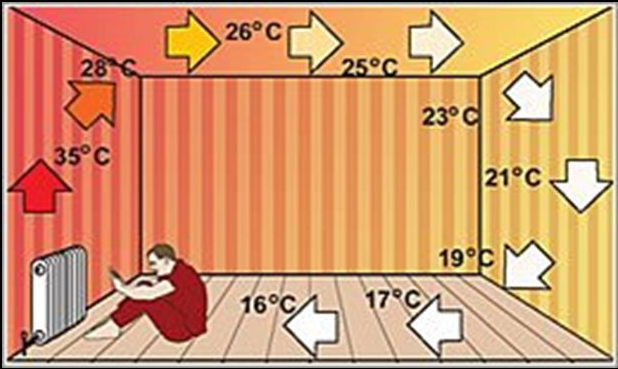

Indoor Natural Convection and Different Rayleigh Numbers

- Natural Convection

Natural convection is a condition in which there is no external driving force but the fluid is still in motion. In natural convection, the fluid surrounding the heat source receives heat and becomes less dense and rises by thermal expansion. Then the cooler fluid moves around to replace it. The cooler fluid is then heated, and the process continues, which creats convection currents.

Natural convection plays an important role in earth sciences, such as atmospheric sciences, oceans, and the earth's mantle. Indoor heating, which we often used, is to use this principle to form complex indoor heat transfer mechanism. In this module, I ues finite volume numerical method to analyze the fluid temperature field, flow field distribution characteristic under different Rayleigh numbers, in order to study the indoor natural convection and heat transfer process.

- Governing equation

Continuity equation:

∂ρ/∂t+∇∙(ρv)=0

Navier-Stocks:

Inertial forces = viscous forces +body forces - pressure gradient

ρ (dv)/dt = μ∇² v + ∆ρg - ∇P

Because temperature affects fluid density, buoyancy changes the term of force in the N-S equation.

ρ (dv)/dt = μ∇² v + ∆ρgα(T-T0) - ∇P

v : vector of fluid velocity; P: pressure; T: temperature; T0: a reference temperature; g: gravity acceleration; ρ: reference density; μ: dynamic viscosity; and α: coefficient of volumetric thermal expansion.

- Model setup

We defined a 1m*1m square cavity filled with the fluid we defined above (reference pressure p=0, reference temperature T0=0). The four sides are no-sliping Wall. The right side is constant temperature (T{0=0), and the lower right wall and bottom edge 0.1m*0.1m are heat sources (T=1). Pressure Point Constraint with the four corners set to p=0.We use this model to simulate the natural convection of indoor enclosed space caused by heating (modified from Buoyancy Flow in Free Fluids by COMSOL Multiphysics).

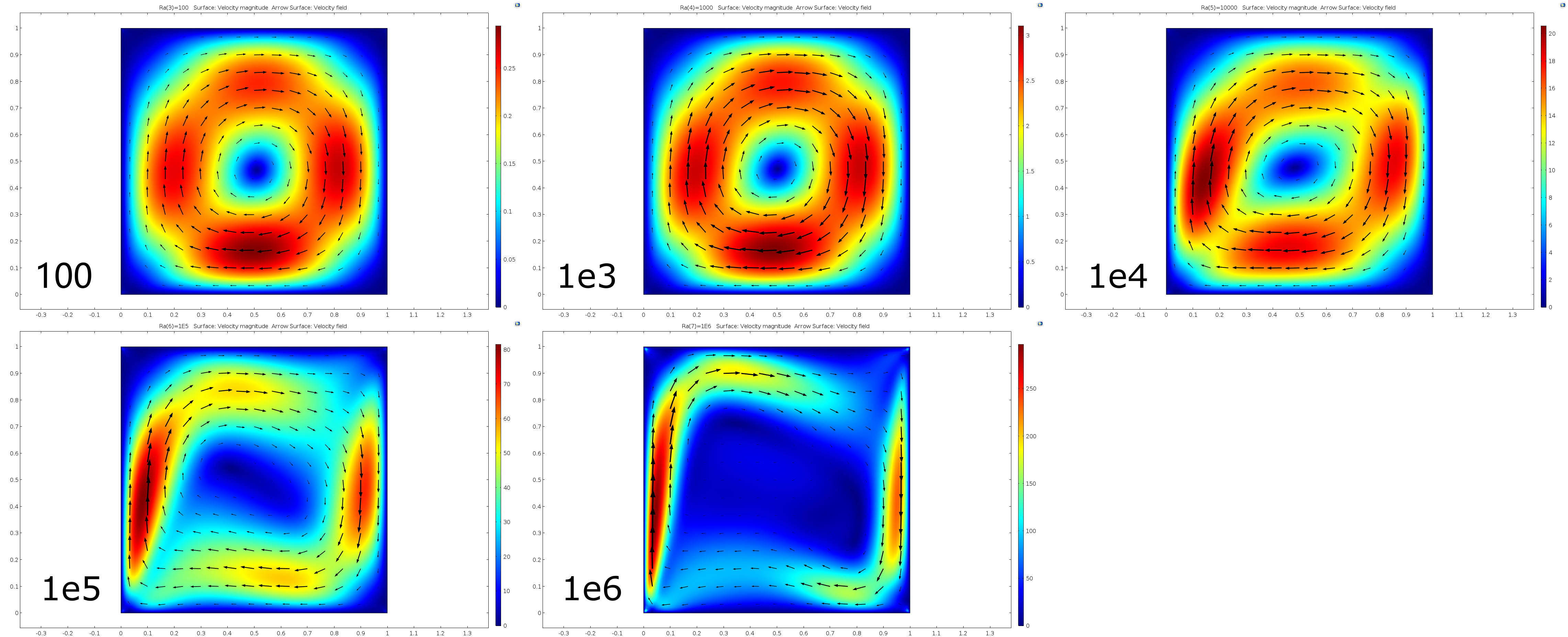

I examine a wide range of scenarios sequencing through different values of Ra using an Auxiliary sweep with continuation selected for the Ra parameter in the Stationary study step (Ra=[100 10e3 10e4 10e5]). With the increase of Ra, the importance of viscous force decreases.

For the convenience of numerical simulation, I defined a fluid that does not exist in reality, whose fluid parameters are shown in the following table:

| Name | Value |

|---|---|

| ρ | 1 |

| μ | 1 |

| k | 1 |

| Pr | 0.71 |

| Ra | Changed as setting |

So numerically (ignoring units) :

Cp=Pr

body force in the y-direction for the momentum equation:

F=(Ra/Pr)(T-T0)

- Result and Discussion

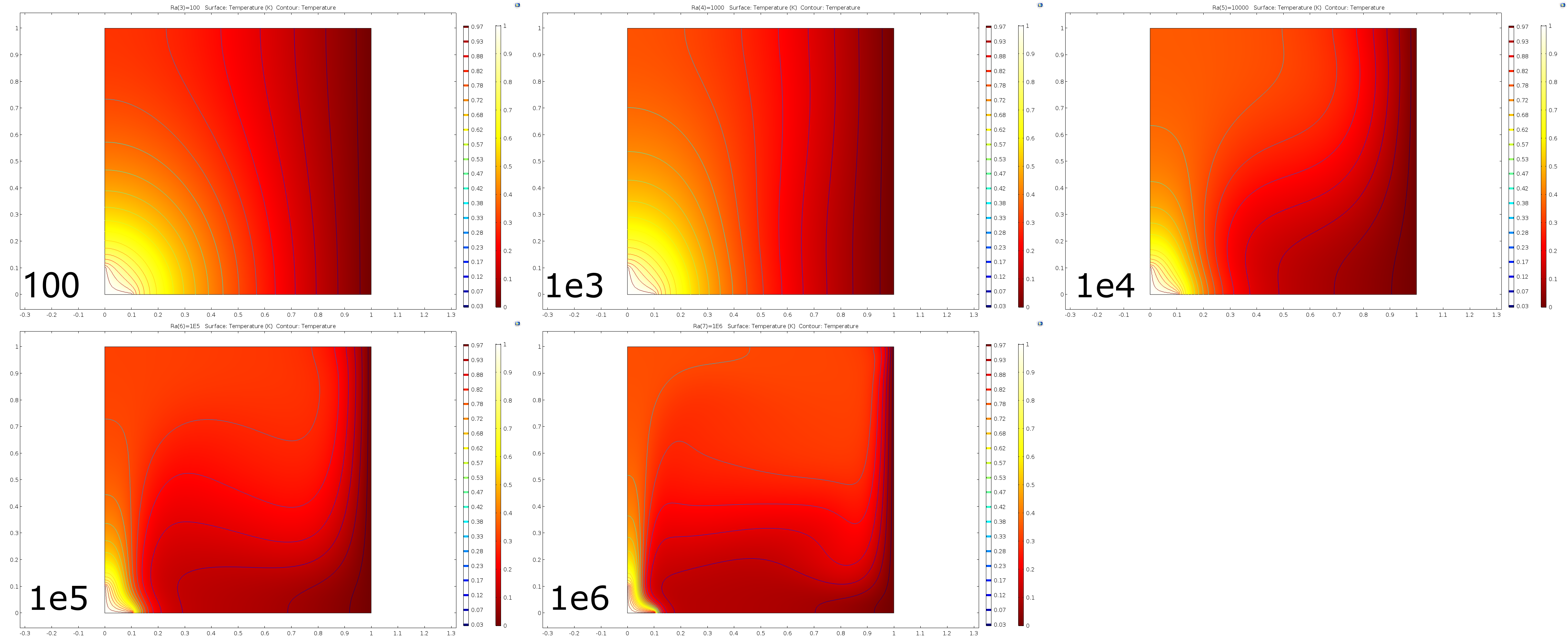

We analyze our results from the aspects of velocity field and temperature field. Free convective flow is completely caused by temperature difference and the velocity field is generated by the temperature field and in turn affects the temperature field.

- Time to stable state

We found that with the increase of Ra, the time of heat transfer to the relatively stable state within the space became shorter.

Ra=100 (in 250ms)

Ra=1e4 (in 130ms)

Ra=1e6 (in 70ms)

- Velocity field

With the increase of Ra, the flow velocity of the fluid in stable state also increases significantly. Convection is near the boundary layer near the hot (cold) wall. Due to the influence of the heat source area on the left, the fluid flows upward along the left wall surface to the top of the square cavity. Due to the limitation of the height of the adiabatic wall surface, the flow line turns to the right. Due to the influence of the right cold wall, the fluid flows down the right cold wall to the bottom of the square cavity. Due to the limitation of the height of the adiabatic wall, the streamline turns left and flows to the left hot wall. The whole flow field flows in a clockwise direction. When Ra= 1e3, there is a vortex at the center of the flow field. With the increase of Rayleigh number, the vortices in the flow field are divided into two symmetrical vortices and move towards the hot (cold) wall continuously.

- Temperature field

Convective heat transfer is the result of the combined action of fluid flow and heat conduction between fluid and molecule. When Ra = 100 or 10e3 (relatively low), the isotherm is uniformly arched outward with the heat source as the center, and the temperature gradient near the heat source is large. With the increase of Ra, the heat transfer changes from heat conduction to heat convection, and the isotherm gradually bends and deforms, forming a thin boundary layer near the cold wall and the heat source.

Heat Transfer in Ice Stream Shut Down and Start (based on Joughin and Alley, 2011)

Stop and start of ice streams is dependent on:

- Thinning (steepens basal temperature gradients)

- Basal freezing (puts on the brakes for a system)

- Thickening (build up traps geothermal heat)

- Ice stream activation & the cycle is repeated

Watch the video below to walk through the steps of ice stream shut-down and speed-up, and see how this relates to the heat transfer equation introduced above.

Further reading:

Different theories exist for ice stream shut down, and here we present varying hypothesis. Please note that the behavior we model in our video is based upon the hypothesis of Joughin and Alley (2011).

- Joughin, I., and R. B. Alley (2011) Stability of the West Antarctic ice sheet in a warming world. Nature Geosci., 4, pp. 506–513. https://www.uib.no/sites/w3.uib.no/files/attachments/joughinnatgeoreview2011.pdf

- Anandakrishnan, S., Alley, R.B., Jacobel, R.W. and Conway, H. (2001) The flow regime of Ice Stream C and hypotheses concerning its recent stagnation. The West Antarctic Ice Sheet: Behavior and Environment, AGU Antarctic Research Series, 77, pp. 283-296. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/H_Conway/publication/266340045_The_Flow_Regime_of_Ice_Stream_C_and_Hypotheses_Concerning_Its_Recent_Stagnation/links/54f92db90cf210398e979b18.pdf

- Catania, G.A., Scambos, T.A., Conway, H. and Raymond, C.F. (2006) Sequential stagnation of Kamb ice stream, West Antarctica. Geophysical Research Letters, 33(14). https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL026430

- Hulbe, C. & Fahnestock, M. (2007) Century-scale discharge stagnation and reactivation of the Ross ice streams, West Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res.-Earth 112, https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1029/2006JF000603

- Lipovsky, B., and E. Dunham (2016) Tremor during ice-stream stick slip, Cryosphere, 10(1), pp. 385–399. https://www.the-cryosphere.net/10/385/2016/tc-10-385-2016.html

- Price, S.F., Bindschadler, R.A., Hulbe, C.L. and Joughin, I.R. (2001) Post-stagnation behavior in the upstream regions of Ice Stream C, West Antarctica. Journal of Glaciology, 47(157), pp. 283-294. https://doi.org/10.3189/172756501781832232